If they are not, it’s a brilliant satire.Įlie Wiesel spent his early years in a small Transylvanian town as one of four children. If the authors are serious, this is a silly, distasteful book. To ask why this is so would be a far more useful project. The world may be like this at times, but often it isn’t. We are told, for instance, to “be conspicuous at all cost,” then told to “behave like others.” More seriously, Greene never really defines “power,” and he merely asserts, rather than offers evidence for, the Hobbesian world of all against all in which he insists we live. While compelling in the way an auto accident might be, the book is simply nonsense. Quotations in the margins amplify the lesson being taught. Each chapter is conveniently broken down into sections on what happened to those who transgressed or observed the particular law, the key elements in this law, and ways to defensively reverse this law when it’s used against you. Each law, however, gets its own chapter: “Conceal Your Intentions,” “Always Say Less Than Necessary,” “Pose as a Friend, Work as a Spy,” and so on. These laws boil down to being as ruthless, selfish, manipulative, and deceitful as possible. This power game can be played well or poorly, and in these 48 laws culled from the history and wisdom of the world’s greatest power players are the rules that must be followed to win. We live today as courtiers once did in royal courts: we must appear civil while attempting to crush all those around us. The authors have created a sort of anti-Book of Virtues in this encyclopedic compendium of the ways and means of power.Įveryone wants power and everyone is in a constant duplicitous game to gain more power at the expense of others, according to Greene, a screenwriter and former editor at Esquire (Elffers, a book packager, designed the volume, with its attractive marginalia). Lurid dreams of hybrids and mutants fill out a book also concerned with "cuteness ratings." The hipster's (and hepcat's) answer to Cleveland Amory. Of course, Burroughs adds some incoherent stuff about dogs (with their "vilest coprographic perversions") and about cats as natural enemies of the State. And then there are Burroughs's cats-Ruski, Fletch, Horatio, Wimpy, et al.-none of whom does anything beyond acting like a cat.

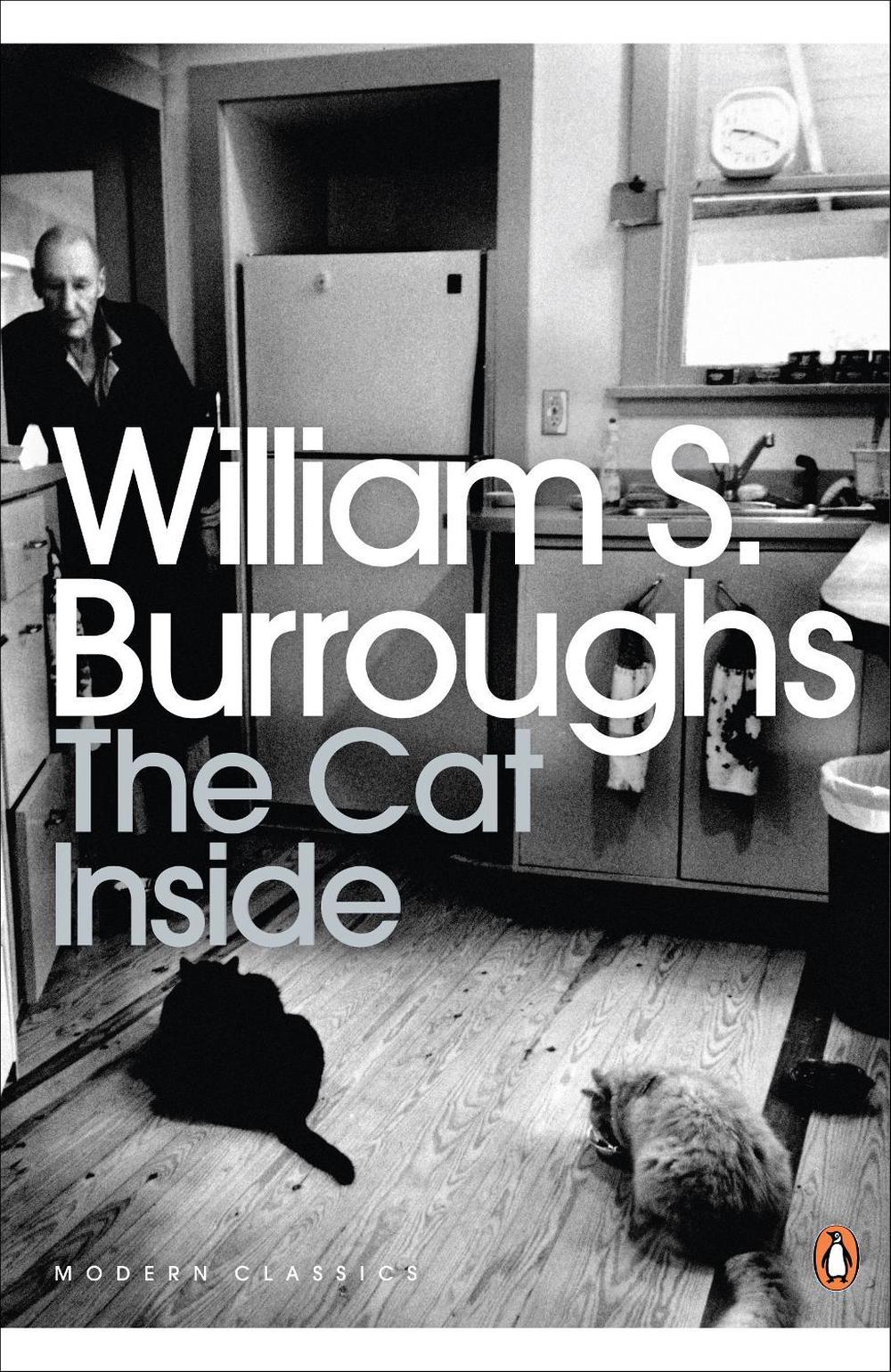

The usual gang of suspects makes the briefest of cameos, from Allen Ginsberg to Jane Bowles. The septuagenarian beatnik would seem to be the least likely author of a cat book, but Burroughs has clearly mellowed some and here celebrates his favorite "psychic companions." Full of sentimental anecdotes and bizarre pseudo-scholarly lore, his slim essay is, in his view, "an allegory, in which the writer's past life is presented to him in a cat charade." Fans will indeed appreciate the references to beat legend, and the cats who witnessed those days in Tangier, Morocco, and Mexico City.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)